We have moved!

Thank you for following the work of the UACES CRN on the European Research Area! We have now moved — please continue to follow our work at:

http://ecprknowledgepolitics.com/

Thank you for all your support!

Wrapping up the UACES CRN on the European Research Area: Summary of the final workshop

Mari Elken and Jens Jungblut

On the 3rd and 4th of March 2016, the European Research Area CRN had its final workshop at the Directorate General for Research & Innovation of the European Commission in Brussels, Belgium. Building on the diverse activities and encompassing research that has been conducted within the framework of the CRN, the workshop had two main aims: to present the research that the CRN facilitated, and to draw lessons from the results of the presented studies which can be of use for policymakers in the European Union. The invitation from DG Research and Innovation provided a common arena for both researchers and policymakers to openly discuss the policy implications of the work of participating CRN members.

In her introduction to the workshop, Meng-Hsuan Chou (NTU Singapore) reminded the audience of the diverse activities that the CRN undertook in the last years. While this was the final event for the CRN, she announced that the network will continue its work in the form of a Standing Group of the European Consortium for Political Research—the Politics of Higher, Research, and Innovation Standing Group.

Jens Jungblut & Pauline Ravinet (Photo credit: Mari Elken)

In the first presentation Martina Vukasovic (University of Gent, Belgium), Mari Elken (NIFU, Norway) and Jens Jungblut (INCHER Kassel, Germany) used the results from five different but related research projects to unpack the multi-level and multi-actor dynamics of higher education policymaking in Europe. The topics discussed included the growing role of stakeholder organisations for policymaking on the European level, and how these organisations shift their own positions as a result of their involvement in European debates. Additionally, conditions for Europeanisation, both with regard to the translation of European policies to national and institutional settings, and European policymaking in the area of education that goes beyond the principal of subsidiarity have been presented. Furthermore, the changing governance of the Bologna Process throughout its development and the withering political salience of the process especially for EU member countries were highlighted in their presentation. Finally, and turning to the national level, the growing importance of political parties and their preferences for national higher education policymaking has been discussed linking also developments on the national level to potential effects for European discussions. Overall, the authors highlight through their different projects that change in European higher education policy does not unfold in a linear manner and that it takes time for policy change to materialise. Furthermore, it became clear that politics increasingly matter, be it due to a growing relevance of political parties or due to increasingly important stakeholder organisations. Finally, also sectoral dynamics and actors and their expertise have an important role to play in European policymaking for higher education.

Albert Sanchez-Graells (University of Bristol Law School, UK) presented a paper that was co-authored with Andrea Gideon (National University of Singapore) that addressed the question of how far and under which circumstances UK universities are bound by EU public procurement rules. Taking the confusion in British higher education about the degree to which UK universities are bound by European rules on public procurement as a starting point, their paper analyses the legal situation both with regards to the universities’ role as buyer of goods and services but also as providers of services in teaching and research. The decreasing level of national regulations in the UK in the context of market oriented governance reforms actually led to a growing importance of European regulations that are still present and valid for the universities even after national changes in the governance arrangements. Thus, marketisation did not free the universities from public procurement rules. On the contrary, the authors concluded that both in the case of universities acting as buyers as well as in situations where universities provided services in teaching and applied research they are in theory bound by EU public procurement rules. Only in the case of basic research the universities’ activities are clearly non-economic by nature and thus public procurement rules are less relevant in these cases. The paper thus presents an interesting case where European regulations and the lack of awareness of these create risks of litigations and liabilities for British universities and partly contradict national governance reforms.

Albert Sanchez-Graells & Andreas Dahlen (Photo credit: Mari Elken)

The second day of the workshop began with a presentation from Meng-Hsuan Chou (NTU Singapore) and Pauline Ravinet (University of Lille 2, France). They provided new insights from an ongoing project about higher education regionalism. Their project has a dual aim of contributing to knowledge in two distinct research fields: new regionalism in international relations and EU studies, as well as higher education policy studies. Both of these sets of literature have traditionally had some limitations—literature on new regionalism has had limited empirical evidence, and literature on higher education policy studies in Europe has frequently been viewed as a unique case of integration. Consequently, there is also limited understanding of the similarities and differences between regional integration initiatives in Europe, Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Analytically, their work builds on three main dimensions: constellations of actors; institutional arrangements and policy instruments; ideas and principles underpinning these structures. During their presentation they showed initial results from their ongoing empirical work. They indicate that while Bologna is widely assumed to have been ‘exported’ to other regions, the so-called Bologna diffusion narrative has been somewhat overstated. While Bologna has created momentum, it is not a stable model that is being emulated. Furthermore, a number of the initiatives in East Asia also pre-date the Bologna Process. In their presentation, Chou and Ravinet showed how regional integration processes in Europe and South East Asia employ a rather similar policy toolkit, raising important questions of the scope and nature of regional integration processes. Overall, the project provides a much-needed comparative perspective to examining regional integration processes. The discussion that followed the presentation raised important questions of the future of the Bologna Process.

Nicola Francesco Dotti (Photo credit: Mari Elken)

In the next presentation, Nicola Francesco Dotti (Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium) examined Framework Programmes (FP) participation from a geographical perspective. The starting point for the presentation was that there is a widespread assumption of uneven spatial distribution of research and development, less is known about how this geography evolves. The aim of the analysis was to identify the drivers for this spatial distribution, examining notions such as diversification vs specialisation, advanced vs. lagging regions and the role of the cohesion policy. During the presentation, insights from two separate sets of analysis were presented, examining regional distribution of FP and spatial dimensions of knowledge brokerage. The first analysis examined regional drivers in the NUTS3 regions in the time period of 1999 to 2010 across six FP themes. The key finding was that there is a link between economic development and success with FP, thus there is higher rate of participation in FP in more advanced regions. Furthermore, the relationship is also evident for regions that are growing (increase) or in decline (decrease). In addition, smart specialisation appears to have little effect in FP participation. The second analysis focused on knowledge brokers, and in particular the Brussels region. While most regions have remained rather stable in their FP performance, Brussels had significantly improved its performance in FP participation (+1,2% from FP5 to FP7). Dotti argued that despite high level of fragmentation of Brussels as a region, the high number of knowledge brokers that the Commission attracts creates a unique benefit in that it creates a very fertile market for access to strategic information, thus benefiting the region.

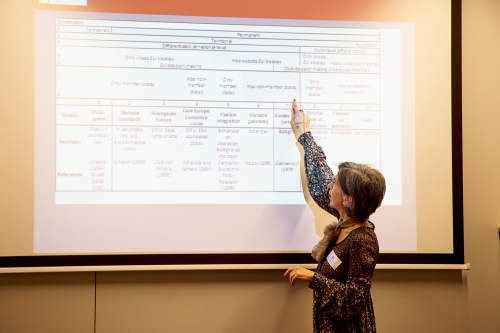

Amelia Veiga (CIPES, Portugal) presented a joint study, with António Magalhães and Alberto Amaral, about the Bologna Process through the lens of differentiated integration, specifically via the process of enactment. They highlight that the Bologna Process has shifted from being a means to something and has become an end in itself. As empirical evidence across Europe shows that there is persistent variation in how the process is implemented on national level, this raises questions of how to tackle this divergence if the aim of the process is convergence. In their study, they find multiple connection points between the main structure of the process, and how it has been implemented across Europe. They mapped the Bologna Process according to the heuristic of various modes of differentiated integration, and found that, in the existing literature on differentiated integration, Bologna can best be placed under Europe a la carte, being a case of a permanent process, with territorial integration process, where differentiation primarily takes place on national level. It is also placed outside of EU treaties, included members beyond the EU, and uses an intergovernmental decision-making mode. From this perspective, Veiga emphasised the necessity to analyse policy implementation as a process of enactment to further understand the tensions created by differentiated integration and the kinds of translation and interpretation processes this creates on national level. Rather than viewing policy analysis as a uniform process across Europe, this calls for more idiosyncratic analysis. Indeed, to look at what is happening on the grounds.

Amelia Veiga (Photo credit: Mari Elken)

Inga Ulnicane (University of Vienna, Austria) and Anete Vitola (University of Latvia, Latvia) then presented their joint study, with Julia Melkers (Georgia Tech, USA), on the notion of scientific diaspora. In the presentation, Inga Ulnicane first offered the results of a literature review that examined the definition of scientific diaspora as a concept, and the various roles it takes. These studies highlight the contradictory nature of the concept—as it emphasises an universalist view on science accompanied with a sense of allegiance to home country. Furthermore, diaspora can take multiple roles, being collaborative knowledge brokers, organising networks or supporting capacity building in home countries. In the presentation, Ulnicane indicated that specific scientific diaspora policies can now be identified in a number of countries, as well as international organisations, such as UNDP. As a case study, the researchers presented their analysis of scientific diaspora policies from Latvia. Latvia provides an interesting case for analysis as it has in recent times experienced a wave of emigration after joining the EU. It is also a country where there is considerable emphasis on using EU funds for capacity building and PhD education. Anete Vitola presented the results from the Latvian case study, showing a shifting policy focus on how diaspora policies were conceptualised. While initially these policies only emphasised on maintaining Latvian culture abroad, focus on scientific and business cooperation has emerged.

The final presentation of the day was from Charikleia Tzanakou (University of Warwick). She argues that knowledge policies are becoming increasingly in the forefront, thus the question ‘knowledge policies for whom’ becomes increasingly pressing. The presentation was based on a mixed methods study on examining career trajectories of Greek PhD graduates from natural sciences and engineering. Tzanakou argued that PhD graduates are a very uniquely placed group, as they are the user, output, beneficiary, and even ‘victim’ of knowledge policies. In the presentation, she highlighted that the rhetoric of ‘we need more PhD graduates’ is not met with appropriate measures for how the labour market is able to absorb them. In the study, she had found that there was considerable under-utilisation on national level, as industry was not always interested in hiring PhD graduates. Overall, the job opportunities in Greece were in many cases limited—both in academia and in industry. At the same time, the number of PhD graduates in Greece has been on the increase, among other things due to EU funding. She highlighted a number of policy implications of the analysis, in particular regarding the nature of the market of researchers in Europe: is the market really open or are we witnessing an increasingly segregated market? The presentation was followed by a lively and interesting discussion regarding the aims and organisation of PhD education in various European countries.

Overall, the workshop included a variety of topics concerning the key elements of Europe of Knowledge, highlighting the complexity of its multi-issue, multi-level, and multi-actor nature. At the same time, the experience also showed how these themes are interlinked, and how inputs from various fields are extremely relevant for advancing our collective insights on the construction of the European knowledge landscapes. The UACES CRN on the European Research Area thus provided an important arena to engage in cross-boundary work and to further the debates on knowledge policies across traditional sectoral divides within and beyond Europe. In the closing remarks, the European Commission representative Andreas Dahlen highlighted the positive experiences from the two days, expressing his wishes that this workshop could be the start for other kinds of knowledge exchange in the future. While this was the final event for the UACES CRN on the European Research Area, the network will continue to engage with scholars and practitioners in the newly established ECPR Standing Group on the Politics of Higher Education, Research, and Innovation.

Summaries & slides from the workshop

- 2016 Brussels workshop ABSTRACTS

- 1 Actors and Institutions in the EoK

- 2 When are Universities bound

- 4 Knowledge Brokerage

- 5 Differentiated Integration and BP

- 7 Knowledge policies for whom

Researching the Europe of Knowledge: Insights for policymakers from the UACES CRN

3-4 March 2016

Directorate General Research & Innovation, European Commission, Square Frère Orban, 8, Brussels, Belgium

Please contact Vicente Andreo Pallares (Vicente.ANDREO-PALLARES [at] ec.europa.eu) if you would like to attend. Seating is limited.

We would like to thank UACES and the Directorate General Research and Innovation, European Commission for generously supporting this event

Programme

Day 1: 3 March 2016

Welcome – Dr Meng-Hsuan Chou (NTU Singapore) – 16.00-16.15

‘Actors and Institutions in the Europe of Knowledge’ – Dr Mari Elken (NIFU), Mr Jens Jungblut (University of Oslo), Dr Martina Vukasovic (Ghent University) – 16.15-17.00

‘When are universities bound by EU public procurement rules as buyers and providers? – English universities as a case study’ – Dr Andrea Gideon (NUS), Dr Albert Sanchez-Graells (University of Bristol Law School) – 17.00-17.45

Day 2: 4 March 2016

‘The Rise of Higher Education Regionalism’ – Dr Meng-Hsuan Chou (NTU Singapore) and Dr Pauline Ravinet (University of Lille 2) – 10.00-10.45

‘Knowledge Brokerage and FP participation: a geographical perspective’ – Dr Nicola Francesco Dotti (Vrije Universiteit Brussel) – 10.45-11.30

‘Differentiated Integration and the Bologna Process’ – Dr Amelia Veiga (Centre for Research on Higher Education Policies) – 11.30-12.15

Lunch – 12.15-13.30

‘Scientific Diaspora: Roles and Options for Knowledge Policies’ – Dr Inga Ulnicane (University of Vienna), Dr Anete Vitola (University of Latvia), and Dr Julia Melkers (Georgia Tech) – 13.30-14.15

‘Knowledge policies for whom?’ – Dr Charikleia Tzanakou (University of Warwick) – 14.15-15.00

Closing remarks – Dr Meng-Hsuan Chou (NTU Singapore) – 14.15-15.00

What is higher education regionalism? And how should we study it?

Meng-Hsuan Chou and Pauline Ravinet

Higher education is undeniably global. But this did not prevent interested policy actors, meeting on the occasion of the 650th anniversary of the University of Vienna in 2015, to emphasise the significance of the global and international dimension, as their colleagues have done at the 800th anniversary of the University of Paris nearly 20 years ago. As academics, we know that higher education has a deep relationship with globalisation: from rankings to mobility of students, faculty, and staff; from quality assurance to student-centred learning outcomes; from university governance to the digitalisation of teaching and research collaboration. It is nearly impossible to separate the two. Yet we are still lacking a clear and shared definition of ‘global’ and ‘globalisation’ among higher education practitioners, scholars, and observers—the very people who have been struck by their intensifying relationship since the very beginning, whenever that was. Our handbook chapter develops a set of conceptual tools and lenses to understand the global transformation of the higher education sector by focussing on a particular pattern of this phenomenon we call higher education regionalism (Chou and Ravinet 2015).

Scanning the globe, we see regional initiatives in the higher education sector. For instance, in Europe, we have the Bologna Process towards a European Higher Education Area, familiar to the readers of this blog. But there are many more. Indeed, there have been consistent efforts in building common areas in Africa: the African Union’s harmonisation strategy, sub-regional initiatives of the Southern African Development Community, and activities of the African and Malagasy Council for Higher Education. Similarly, in Latin America, there is the ENLACES initiative, the MERCOSUR mechanisms for programme accreditation (MEXA) and mobility scheme (MARCA). Looking East to Asia, there are the many initiatives from the AUN and the very exciting SHARE programme. These are manifestations of higher education regionalism, which we define as referring to:

[A] political project of region creation involving at least some state authority (national, supranational, international), who in turn designates and delineates the world’s geographical region to which such activities extend, in the higher education policy sector (Chou and Ravinet 2015: 368).

We derived this definition after a review of what has been written on higher education regionalism in political science and in higher education studies—two distinct sets of literature that have much to say about this phenomenon, but rarely engage each other in a fruitful conversation on the subject. From political science, we learned from scholars who examined regions, ‘new regionalism’, and European integration (Caporaso and Choi 2002; Fawcett and Gandois 2010; Hettne 2005; Hettne and Söderbaum 2000; Mattli 2012; Warleigh-Lack 2014; Warleigh-Lack and Van Langenhove 2010). From higher education studies, we obtained insights from scholars who are serious about the impact that the re-composition of space, scales, and power have on past, current, and the future state of higher education (Gomes, Robertson and Dale 2012; Jayasuriya and Robertson 2010; Knight 2012, 2013).

The lessons from our review led us to these three positions concerning the study of higher education regionalism:

- It must be comparative. Studying higher education regionalism means comparing varieties of higher education regionalisms to consider the sector’s apparent isomorphism.

- It must be sector-based. Studying higher education regionalism is to take serious the particular dynamics of higher education and how they interact with the wider multi-purpose regional organisation (EU, ASEAN, AU, etc.) and national needs.

- It must be differentiated. Studying higher education regionalism means to distinguish between intra-regional initiatives (within one geographical region) and inter-regional initiatives (between at least two geographical regions).

With these points of departure, we proposed a heuristic framework to study higher education regionalism along these three dimensions:

- Constellation of actors central and active in these processes: this means identifying the individual and collective actors involved and mapping their interaction patterns.

- Institutional arrangements adopted, abandoned, and debated: this refers to identifying the institutional form and rules and the instruments considered and accepted.

- Ideas and principles embedded and operationalised: this points to identifying the paradigms, policy ideas, and programmatic ideas guiding the instances of higher education regionalisms.

These three dimensions require intensive fieldwork with the key actors involved, which we are currently undertaking in the Southeast Asia region. But we invite researchers—especially those examining less studied regions such as Africa and Latin America—to get in touch so that together we can contribute to the conversation about higher education and globalisation from the regional perspective.

Meng-Hsuan Chou is Nanyang Assistant Professor of public policy and global affairs at NTU Singapore and Pauline Ravinet is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Lille 2. They both acknowledge the generous support from Singapore’s Ministry of Education AcRF Tier 1 and Institut Français de Singapour (IFS) and NTU Singapore’s Merlion grant for this research.

References

Caporaso, J. A. and Y. J. Choi (2002) ‘Comparative regional integration’, in W. Carlsnaes, T. Risse and B. A. Simmons (eds) Handbook of International Relations (pp. 480–500) (London: Sage).

Chou, M.-H. and P. Ravinet (2015) ‘The Rise of “higher education regionalism”: An Agenda for Higher Education Research’ in J. Huisman, H. de Boer, D.D. Dill and M. Souto-Otero (eds) Handbook of Higher Education Policy and Governance (pp. 361-378) (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan).

Fawcett, L. and H. Gandois (2010) ‘Regionalism in Africa and the Middle East: Implications for EU studies’, Journal of European Integration, 32(6), 617–636.

Gomes, A. M., Robertson, S. L. and R. Dale (2012) ‘The social condition of higher education: Globalisation and (beyond) regionalisation in Latin America’, Globalisation, Societies and Education, 10(2), 221–246.

Hettne, B. (2005) ‘Beyond the “New” regionalism’, New Political Economy, 10(4), 543–571.

Hettne, B. and F. Söderbaum (2000) ‘Theorising the rise of regionness’, New Political Economy, 5(3), 457–472.

Jayasuriya, K. and S. L. Robertson (2010) ‘Regulatory regionalism and the governance of higher education’, Globalisation, Societies and Education, 8(1), 1–6.

Knight, J. (2012) ‘A conceptual framework for the regionalization of higher education: application to Asia’, in J. N. Hawkins, K. H. Mok and D. E. Neubauer (eds) Higher Education Regionalization in Asia Pacific (pp. 17–36) (New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

Knight, J. (2013) ‘Towards African higher education regionalization and Harmonization: functional, organizational and political approaches’, International Perspectives on Education and Society, 21, 347–373.

Mattli, W. (2012) ‘Comparative regional integration: Theoretical developments’, in E. Jones, A. Menon and S. Weatherill (eds) The Oxford Handbook of the European Union (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Warleigh-Lack, A. (2014) ‘EU studies and the new Regionalism’, in K. Lynggaard, K. Löfgren and I. Manners (eds) Research Methods in European Union Studies (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

Warleigh-Lack, A. and L. Van Langenhove (2010) ‘Rethinking EU Studies: The Contribution of Comparative Regionalism’, Journal of European Integration, 32(6), 541–562.

This entry was initially posted on Europe of Knowledge blog.

CFP: Transnational actors in knowledge policies – ideas, interests and institutions (2016 ECPR)

Panel: Transnational actors in knowledge policies – ideas, interests and institutions

- Co-chairs: Tatiana Fumasoli (University of Oslo) – tatiana.fumasoli@iped.uio.no and Martina Vukasovic (Ghent University) – Martina.Vukasovic@ugent.be

- Co-discussants (TBC): Åse Gornitzka (University of Oslo) and Simona Piattoni (Universty of Trento and University of Agder)

Apart from supranational and intergovernmental dynamics, European knowledge policy-making is marked also by a transnational dimension related to the involvement of non-state actors in decision-making (Elken & Vukasovic, 2014; Fumasoli, 2015b; Piattoni, 2010). These non-state actors are often organized across nation-states and include both collective actors – academic and university associations (e.g. European Academies, European University Association), students and staff unions (e.g. European Students Union, Education International), funding and quality assurance agencies (e.g. European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education) – and individuals (experts and individuals working for the collective actors).

Some of these are, in organizational studies’ terminology, meta-organizations (organizations of organizations) with complex internal structures, membership and identity (Ahrne & Brunsson, 2008). We consider meta-organizations those organizations that have institutional membership exclusively, or have institutional membership along with individual membership. In political science, such organizations are considered to be interest groups, organizations with an explicit political mandate to influence decision-makers at various governance levels (Beyers, Eising, & Maloney, 2008). They are often seen as spokespersons of the various stakeholders, expected to increase the legitimacy of decisions made (Moravcsik, 2002; Neave & Maassen, 2007). In addition, these organizations provide communication platforms and can act as sites of social learning and persuasion about appropriateness of specific ideas, norms and values, thus facilitating cross-national policy platform and socialization of actors (Checkel, 2003; Voegtle, Knill, & Dobbins, 2011). A perspective from the sociology of professions characterizes these transnational organizations as pursuing professional development, protecting their professional jurisdiction, and fostering their professional identity (Freidson, 2001; Larson, 2013). Those are traditionally structured around scientists- and scholars’ individual membership, and focus on a distinctive discipline. However these organizations might display multiple types of membership as well (Fumasoli, 2015a), and might activate themselves as interest groups, insofar they consider that their concerns need to be addressed in policy arenas (Truman, 1993 cited in Beyers et al., 2008, p. 1107).

Apart from operating across nation-states, these actors also operate across governance levels (e.g. European and national, federal and state), bringing new ideas, advancing the interests of their constituencies and re-shaping the institutional arrangements of policy-making in the area of knowledge. As such, they are uniquely positioned to influence policy formation (including agenda-setting, policy design and policy-decision), as well as policy implementation and policy evaluation.

Yet, despite their important role in governance and societal dynamics in general, such organizations have been the focus of rather limited scholarly interest thus far. The panel welcomes papers exploring how these emerging actors participate in the policy arena and what impact they may have on policy decisions across governance levels. Theoretical and methodological approaches should be clearly presented in the abstract and elaborated on in the paper.

References

Ahrne, G., & Brunsson, N. (2008). Meta-organizations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Beyers, J., Eising, R., & Maloney, W. (2008). Researching Interest Group Politics in Europe and Elsewhere: Much We Study, Little We Know? West European Politics, 31(6), 1103-1128. doi: 10.1080/01402380802370443

Checkel, J. T. (2003). “Going native” in Europe? Theorizing social interaction in European institutions. Comparative Political Studies, 36(1-2), 209-231.

Elken, M., & Vukasovic, M. (2014). Dynamics of voluntary policy coordination: the case of Bologna Process. In M.-H. Chou & Å. Gornitzka (Eds.), The Europe of Knowledge: Comparing Dynamics of Integration in Higher Education and Research Policies (pp. 131-159). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalism : the third logic: Cambridge : Polity.

Fumasoli, T. (2015a). European academic associations: mapping their characteristics, capacity and institutional embedding – preliminary work. Paper presented at the CHEGG seminar, Ghent University.

Fumasoli, T. (2015b). Multi-level governance in higher education. In J. Huisman, H. de Boer, D. D. Dill & M. Souto-Otero (Eds.), The Palgrave International Handbook of Higher Education Policy and Governance (pp. 76-94). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Larson, M. S. (2013). The rise of professionalism : monopolies of competence and sheltered markets. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Moravcsik, A. (2002). Reassessing Legitimacy in the European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 40(4), 603-624. doi: 10.1111/1468-5965.00390

Neave, G., & Maassen, P. (2007). The Bologna Process: An Intergovernmental Policy Perspective. In P. Maassen & J. P. Olsen (Eds.), University Dynamics and European Integration (Vol. 19, pp. 135-153). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Piattoni, S. (2010). The theory of multi-level governance: conceptual, empirical, and normative challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Voegtle, E. M., Knill, C., & Dobbins, M. (2011). To what extent does transnational communication drive cross-national policy convergence? The impact of the Bologna process on domestic higher education policies. Higher Education, 61(1), 77-94. doi: 10.1007/s10734-010-9326-6

This panel is proposed for the 2016 ECPR Section (7-10 September 2016, Prague). If you are interested in participating in this panel please get in touch with the co-chairs.

CFP: Complexity and the politics of knowledge policies: multi-issue, multi-level and multi-actor (2016 RCPP)

Complexity and the politics of knowledge policies: multi-issue, multi-level and multi-actor (Panel T03P05)

Conference: 2016 HKU-USC-IPPA Conference on Public Policy

When: 10-11 June 2016

Where: Hong Kong

Deadline for paper proposal: 30 January 2016

How & where to submit: select T03P05 and upload your proposal at http://www.socsc.hku.hk/webforms/cpphk-paper-proposal-submission-theme3/

If you have any questions, please contact:

Meng-Hsuan Chou (menghsuan.chou@gmail.com)

Jens Jungblut (j.p.w.jungblut@ped.uio.no)

Pauline Ravinet (pauline.ravinet-2@univ-lille2.fr)

Martina Vukasovic (martina.vukasovic@ugent.be)

Complexity and the politics of knowledge policies: multi-issue, multi-level and multi-actor

The complexity of policy processes and the relationship between instrument choice and impact have always intrigued scholars of politics, public policy, and public administration. Indeed, complexity constitutes a key element in established public policy theoretical frameworks such as punctuated equilibrium, multiple streams, and is at the core of Lindblom’s science of ‘muddling through’. In recent years, policy scholars such as Cairney and Geyer have pushed for embracing complexity as a foundation and starting point for policy analysis. These scholars advocate a ‘complexity theory’ approach that enables researchers to attend to both top-down as well as bottom-up dynamics, interests and behaviour of various actors, and how policy ideas, goals and instruments are interpreted and transformed during the policy process.

This panel engages with the complexity approach in public policy through the case of knowledge policy, which refers to basic and applied research, innovation, and higher education. The issues at the core of these policy areas are cross-cutting, which means that their governance does not neatly fall into one single policy domain (multi-issue). Indeed, they often require collaboration across multiple policy sectors as the different aspects of knowledge policies are under jurisdiction of different ministries (multi-actor). Due to increasing processes of international and subnational coordination, developments in the knowledge policy domain are a multi-level endeavour. The case of knowledge policy thus offers a promising empirical avenue to explore the key concepts at the heart of ‘complexity theory’, as well as a bridge for interdisciplinary theoretical exchanges.

We seek submissions that address cross-cutting issues in the knowledge policy domains and the multi-actor and multi-level policy processes involved. Submissions are invited from all theoretical schools using quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods approaches, but should demonstrate a good conceptual understanding of the complexity of knowledge policies with a clear empirical, preferably comparative, focus.

CFP: Policy failures in the knowledge domain (2016 ECPR)

Panel: Policy failures in the knowledge domain

- Chair/discussant: Meng-Hsuan Chou (NTU, Singapore) – menghsuan.chou@gmail.com

Higher education, research, and innovation policy domains have undergone dramatic changes in recent decades. Embedded in these changes are assumptions about failure and learning, and the belief that the ‘new and novel’ would ‘right’ the ‘wrongs’. Yet our understanding of the failure-learning mechanism remains under-developed. Indeed, social scientists often conflate three distinct types of failure—politics, policy, and instruments—in their analyses.

The consequences of failure also remain an on-going question. Do all failures lead to sizeable policy change or to less dramatic reforms or tinkering? Or to no actions at all? While spectacular policy failures are historically memorable, the subtle failures that trigger incremental changes, or indeed the acknowledgement of their very existence, are less examined. For instance, what are the modes of institutional change? To what extent do these changes lead to reform?

The above observations raise several questions about failures and learning in knowledge policymaking which scholars of public policy, comparative politics, international relations, and social sciences in general have only begun to address. These include, but are not limited to: why do some policy failures lead to institutional collapse or abandonment of policy ideas, while others do not? Indeed, why are some policy ideas more sticky than others? To what extent do policy failures shape the institutional design of international, regional, and national, and sub-national decision-making? Is there a cycle of failure and learning involved in the everyday functioning of political and knowledge institutions (e.g. universities and research institutes)? And, if so, how do we first detect and then determine which ‘failure-learning’ mechanism is weak and which one is robust?

This panel invites papers that seek to identify and unpack the failure-learning mechanism operational in specific knowledge policy changes. It welcomes a diversity of approaches – qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods – from all scholars and practitioners interested in the above questions.

This panel is proposed for the 2016 ECPR Section (7-10 September 2016, Prague). Please contact the panel chair before 24 January 2016 with your abstract (300 words) if you are interested in submitting a paper for this panel.

CFP: Applying complex systems theory to higher education and research policy (2016 ECPR)

Panel: Applying complex systems theory to higher education and research policy

- Co-chairs/Co-discussants: Mitchell Young (Charles University in Prague) – young.mitchell@gmail.com and Julie Birkholz (University of Ghent) –julie.birkholz@ugent.be

Describing political and policy phenomena as complex has become commonplace; however, most often the term is used generally without reference to the scientific study of complex systems. Recently several authors have sought to chart out ways by which to apply complexity theory to public policy (Morcol 2012, Room 2011); however, there is still very little being done with these theories and concepts in the areas of higher education and research.

Papers in this panel may take either a qualitative or quantitative approach, but will all rigorously attempt to apply key concepts in complex systems theory (emergence, tipping points, non-linear dynamics, self-organization, fitness landscapes, co-evolution, etc.) to the study of higher education and/or research.

This panel is proposed for the 2016 ECPR Section (7-10 September 2016, Prague). If you are interested in participating in this panel please send the panel co-chairs a 500 word abstract by January 24th. If you have questions or would like to run ideas past them in advance, please feel free to contact either or both of them.

CFP: Researching the governance of knowledge policies: methodological and conceptual challenges (2016 ECPR)

Panel: Researching the governance of knowledge policies: methodological and conceptual challenges

- Co-chairs/Co-discussants: Mads Sørensen (Aarhus University) – mps@ps.au.dk and Mari Elken (NIFU) – mari.elken@nifu.no

Research and higher education policy studies often take the state as a starting point for analysis. Single country case studies and comparisons between individual countries seem to be the most common approaches. At the same time, governance of knowledge policies increasingly takes place in the context of globalisation and regional integration, and is of interest to various international, supranational and transnational organisations. Furthermore, new linkages are developed on sub-national level – in the form of various networks and co-operation constellations. Overall, one can find new forms of vertical and horizontal coordination in the area of knowledge policies. The question then is: how meaningful this single country approach is in an increasingly interconnected world? Does this lead to ‘methodological nationalism’ and limit the scope of analysis? Are there alternative conceptual and methodological approaches to be used, and if so – what would this mean?

We invite papers that examine (empirically, theoretically) the role of the nation state as well as inter-, trans-, supra- and sub-national arenas in knowledge policy studies. We aim to identify sector-specific methodological and conceptual challenges and highlight alternative (multi-level) approaches and foci.

This panel invites papers focused on questions such as: Which role does the nation state actually play in studies of higher education and research policy, and what are the advantages and disadvantages of such an approach? Which other units could we focus on if we want to avoid methodological nationalism and eurocentrism on the one hand but still on the other hand want to compare different policy designs of higher education and research policy? Are there sector-specific conceptual challenges for researching governance of knowledge in a multi-level policy context? What kind of conceptual challenges emerge in studying knowledge policies and linkages across levels and arenas? What are the appropriate approaches and designs for studying increased horizontal and vertical coordination? Where are existing conceptual blind spots? What are the consequences of this for both research design and methodology? What kind of differences in terms of methodology, research design etc. can be identified between higher education and research policy studies? What are the benefits and disadvantages of such approaches?

Papers at this panel could discuss the use of alternative entities than the nation state, including institutions, regions, networks, traditions, ideas, cultures etc. Papers for this panel could also examine the methodologies used in higher education and research policy studies – empirically and/or theoretically, including focus on comparative designs. Suggestions for innovative research designs are also welcome.

This panel is proposed for the 2016 ECPR Section (7-10 September 2016, Prague). Please contact the panel co-chairs before 24 January 2016 if you are interested in submitting a paper for this panel.

CFP: Politics of Access in Higher Education Systems (2016 ECPR)

Panel: Politics of Access in Higher Education Systems

- Co-chairs: Beverley Barrett, University of Houston (beverly.barrett@gmail.com) and Karel Sima, Centre for Higher Education Studies, Czech Republic (karel.sima@centrum.cz)

Expectations for greater access to higher education systems have followed trends reflecting an increasing number of democratic countries in recent decades. Given the acceleration of globalization, with pressure for greater access to higher education, the politics of access for domestic and international students remains contentious for entry into competitive academic programs worldwide. Considering the power of ideas, interests, and institutions, how do specific national goals and policy strategies to increase educational access compare across countries and across regions? In which countries and regions are trends for increasing educational access most innovative and most effective?

We invite contributions that compare and examine the extent to which these higher education access initiatives, across continents, support learning objectives and graduation outcomes that are innovative and effective supporting employability. In recent years, we have observed a proliferation of national and regional strategies for increasing access to higher education around the world: in Africa, Asia, Latin America, North America and Europe. The European drive to consolidate the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), since the early 2000s, has higher education attainment as an explicit objective.

This panel focuses on questions that address how national policy strategies on access confront current issues and developing trends. What are the higher education policies to accommodate domestic and international students towards the goal of increasing access? What are innovative and effective policy instruments, and what have been their impacts across countries and continents? How do unique actors (governments, institutions, academics, students etc.) actively engage in decision-making processes in complex multi-actor environments reflecting distinct preferences and goals?

The wave of higher education expansion in Western world in the 20th century was fuelled by the population growth of post-war baby boomers. This resulted in mass higher education systems in most of the European and American countries. Consequently the student populations have substantially changed reflecting sociocultural diversity. Furthermore, internationalisation has become an objective for higher education in the 21st century in the EHEA and across continents. These trends have changed not only the form and content of higher education, but also education’s role in the knowledge-based economy and society.

The international mobility of students in higher education continues to accelerate. Countries seek to retain talented students, supporting objectives towards national competitiveness, while being open to global talent, overlapping with objectives for internationalisation. As countries become more developed, access issues continue to become more pressing within a knowledge-driven economy. Developing economies that can accommodate increased access to education, at every level, are investing invaluable knowledge creation that leads to productivity.

This panel addresses trends for increasing educational access, identifying innovative and effective national policy strategies that address challenges of the internationalised mass higher education of the 21st century. We invite contributions that would analyse these trends on various levels of governance, and from perspectives of multiple actors, as well as those that employ a comparative approach on international, institutional, and disciplinary levels.

This panel is proposed for the 2016 ECPR Section (7-10 September 2016, Prague). Please contact the panel co-chairs before 24 January 2016 if you are interested in submitting a paper for this panel.